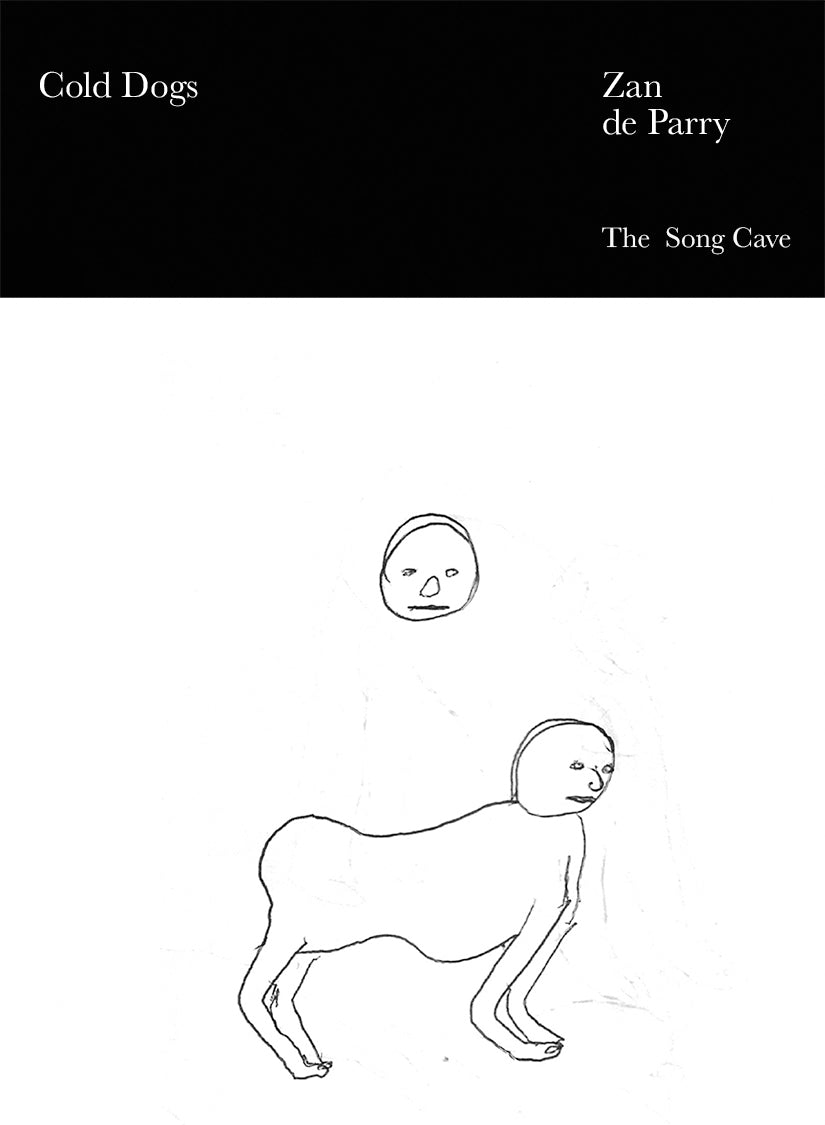

Cold Dogs by Zan de Parry

In “Cruel Extensions,” an early poem in Cold Dogs, the scene is of “enter[ing] the shop of an absent grocer to steal” then getting trapped inside. The speaker never even tries to start stealing, though, they just find that the door closes in on them. They try to break the door, the window breaks “onto” their “face,” and the grocer appears, trying to catch the speaker as the speaker tries to climb out:

And pulls me down to kick me in the head

I’m no prisoner to walking

I walked into the cage of walking willingly

I’ve touched every ad, become brilliantly traceable

Ate food wrapped in bright words as if the food itself could speak

Yesterday I got shot with footprints in my face

The king pulled me down

And kicked me in the head with power

At first I was upset

Because it seemed to reflect the essence

Of what keeps happening

But I don’t want to write like that

I want to live a long, good, hard, young life

This poem has a more overt “message” than most others—or, it more overtly acknowledges that part of their zaniness “reflect[s] the essence / Of what keeps happening.” Note that here Zan confesses he “[doesn’t] want to write like that," meaning (I think): make overt statements against and about how power kicks people in the head, and how that keeps happening. He follows that confession with a closing line that is so earnest yet absurdly placed that it still “says” something about being trapped in the shop of horrors of the world. At first upset—then absurd.

I noticed that these poems usually lack enjambment. This is the case, on one hand, because most first letters are capitalized. (Those capitals had an air of “protest” given how little capitalization is in modern/ist poetry. They were even somewhat humorous, a juxtaposition of classical sensibility with these poems’ content, which I think is fair to say is not "classical.") This lack of enjambment also stems from the poems being less breathy-expression-of-personal-consciousness than stories told by a totally ecstatic person, taking a breath between each surreal, luminous, vulgar, and absurd detail of their story, or a person who just woke up remembering details of their dreams.

The un-enjambed lines and the storytelling quality set you up sometimes to feel like you’re about to get some closure or payoff. Right away, though, that expectation is banished with a poem like “Parson’s Nose,” which closes:

That bone on the inside of your elbow

is called a parson’s nose

and you have a big one.

Now, I admit I may be missing an idiom that would “unlock” the poem (and also happen to have quoted some enjambed lines 😅). However, I hear these lines instead expressing some kind of stance about closure in poetry (aggression, mocking, something else?) rather than a metaphorical take-home. I would laugh at the poem’s close, and do laugh, but it “really makes me think” that there’s something more sinister or maniacal hiding there…

That’s supported by the “mock-closure” of “John the Conqueror,” which insinuates violent childhood experiences and closes:

But brother… brother was an active child

Yes. He was

In our world of self-knowledge and personal coherence, of Instagram post quotes motivating you on your quest for self-improvement, that “Yes. He was” refuses to hem, haw, and give meaning to pain. (“But I don’t want to write like that.")

Where music is concerned, these poems have less of a rhythm than dynamic contrasts (noise poetry?). These dynamic shifts enable instant transformation of emotions between lines, especially rapid intensifications. “Barn Door” is one I kept going back to. It starts sweet, enjambing, cuts off to a rumination about keeping your phone in your pants pocket, then violently turns up, along the way promising to rob you, cook for you, put money into your savings account, and one day buy you a surprise:

You can buy pants with pockets

On the pants. I use these for trips

To pocket-sized places, like my historic homeland

I’ve long realized that keeping my phone in my pocket

Is cost-effective, like living in a barn

Crack open your phone and see

Two people wearing glasses having sex

I can’t wait to take you home and rob you

Break your chaste and taste it with masa

To get a piece of your galore

Show up out of the woods at like 1000 AM

Cook you a boiling plate within seven minutes

Add 25 dollars to a new savings account

Until I can afford you an old, beautiful bridge

In her blurb of Cold Dogs, Jennifer Nelson writes that Zan’s word choice is like “if thesauruses and homophones were used in righteous anger against a world where algorithms have already found substitutes for our words and desires.” This righteous anger is then termed a “conviction that human existence, rendered supple amid closely observed consumerist hellscapes, might follow words in possessing the old gods, and should revel in their poetic flux.”

This excellent reading of the poems reminds me a bit of Deleuze’s idea about foreign language, “which is neither another language nor a rediscovered patois, but a becoming-other of language ... a delirium that carries it off, a witch’s line that escapes the dominant system.” That delirium results from arrangements and syntactical operations that, from the perspective of the symbolic (algorithmic) order, are totally unpredictable, like the rapidly ramping up lines of Cold Dogs.

Intrinsic to such language is a "righteous anger," but that anger ultimately gives way to the aforementioned "flux," in which human-dog sketch-forms are both symptomatic of existence nowadays as well as the start of something other we ought to lean into becoming, lest we retain "the essence / Of what keeps happening."

Comments

Post a Comment