Stroke by Stroke by Henri Michaux

I came across Stroke by Stroke in the wake of reading The Wilds of Poetry, an anthology assembled by David Hinton, a poet and translator of Chinese poetry. In the introduction, he calls attention to writing’s pictographic origin, which ideograms maintained but alphabetic languages abandoned.

Whereas pictographic language “manifest[s] a direct connection to the empirical world,” alphabetic abstraction connects letters to speech sounds, resulting in “words that have an arbitrary relationship to the things they name.” This explains a whole cosmology for Hinton, whereby “consciousness as open and integral to natural process [as in Taoism] was replaced by an immaterial soul ontologically separate from and outside of material reality.” Instead of consciousness being the same as everything else, it is the Ego’s, a detached and reflexive entity that is not the same as the things it thinks about. Alphabetic writing, which “arbitrarily relat[es]” to the things it names, actually negates them. Writing this way results in dissociation without end.

Hinton proposes that certain avant-garde American writers, consciously or unconsciously, seek to reintegrate mind with natural process, even if that’s impossible in alphabetic language. One of the poets Hinton includes is Gustaf Sobin. (Sobin translated Michaux’s Ideograms in China, which led me to Stroke by Stroke.) Hinton helped me understand Sobin’s writing of “emptiness … inscribed” and “unfurled” in terms of Taoism; before reading Wild Mind, however, I’d superficially connected Sobin’s phenomenological bent, his digestion of Heidegger and Char, to a French-language poetics of nothingness, which has Maurice Blanchot as a patron saint.

In The Space of Literature, Blanchot argues that “[the poet] creates a work of pure language … just as the painter, rather than using colors to reproduce what is, seeks the point at which his colors produce being.” In the poetry Blanchot wants, images do not stand for objects, but instead are “appearances” that arise out of the nothingness that language, because it negates, makes appear. I haven’t read enough Blanchot to know what the “solution” to this conundrum is, but I don’t think it’s to insist on a language that manifests a direct connection to the empirical world through ideogrammatic “signs.” However, Blanchot does argue that literature “says exclusively ... that it is—and nothing more,” which would appear to put literature on the side of pure being, rather than a representational something that gives the Ego self-coherence. In fact, Blanchot writes of the true poet: “Where he is, only being speaks—which means that language doesn’t speak anymore, but is.”

Stroke by Stroke, firmly embedded in both lines of questioning, is made up of two separate texts: Grasp and Stroke by Stroke, both translated by Richard Sieburth. Over the course of both, Michaux tries out a variety of justifications for turning away from alphabetic language, each of which results in a different kind of graphic sign system.

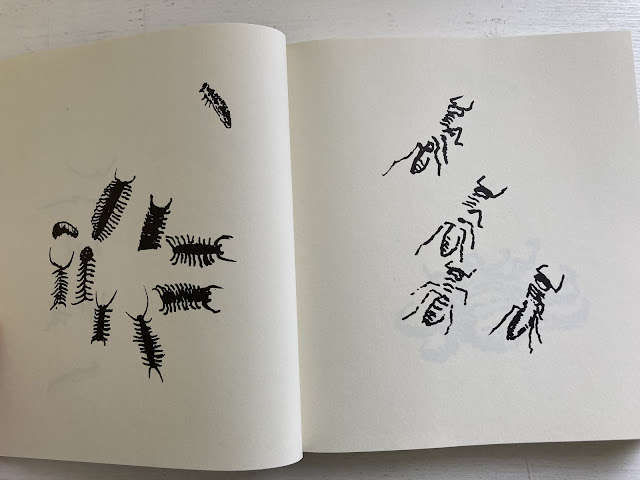

This story starts with Michaux asking: “who has not wished to get a fuller, better, different grasp on [living creatures and things], not with words, not with onomatopoeias, but with graphic signs?” This “grasp” would shed referential, alphabetic language in favor of the following:

Grasp is accompanied by an essayistic text, in which Michaux describes how he has been kept away from “the path of all resemblance” hitherto, implying a la The Wilds of Poetry, that alphabetic language has instantiated a deep feeling of absolute difference from the reality of resemblance. Quickly, Michaux abandons the animal “graspings” to instead grasp for “an inner likeness” that animates “the primal dance of creatures”:

Ultimately, Michaux finds that “everything is translation at every level, in every direction.” Thus, in his quest to dissemble in the name of “grasping” something more fundamental, Michaux “grasps” that writing is intrinsically dissociative, or at least, remains writing, despite whatever else it’s trying to be or connect with.

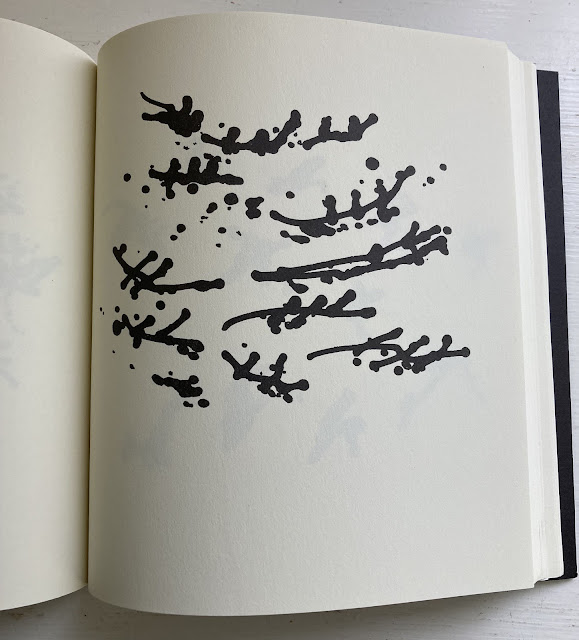

Stroke by Stroke begins with fuller strokes:

In place of a drawing-by-drawing commentary, Michaux embeds a poem that begins with the line “[g]estures rather than signs” and contains the refrain “STROKE BY STROKE.” In the poem, he enthusiastically speaks of “derealiz[ing]” and “insignifying” stroke by stroke:

From morning to night

from unicellular to whale

from harvest to industry

Irreducible, elemental strokes

In his afterword, Sieburth explains that the “strokes” Michaux here describes, which enfold unicellular organisms and massive mammals, time, organic life and manmade industry, could be translated by “the Chinese wen, a character signifying marks, whether these be the veins of stone or wood, the lines that connect stars into constellations, the tracks of animals on the ground, the cracks in tortoise shells used for divination, or finally, the art of writing.”

Thus, in the graphic sign system belonging to this section of the book, Michaux figures writing as a way of feeling the stroke-by-stroke constitution and dissolution of being:

The book ends with Michaux’s essay “On Languages and Writing: Why The Urge to Turn From Them.” The essay has ideogram-like shapes printed across the top margin.

In the essay, Michaux figures alphabetic language, and the abstraction it supports and intensifies, as “sign” of repressive, managerial civilization. This language has as its ultimate end “the power to eliminate the real and the concrete at a single stroke.” Michaux’s graphic signs (gestures) are meant to bring writing back to the place of the “fore-languages … left behind, never to be known,” whose purpose was not managerial, but “distractions of a moment … pleasures of the hunt while killing time.” Graphic signs would “disalienat[e] man,” ostensibly allowing whoever is writing to be closer to experience, playfully responding to their actual moment, unconcerned by the implications of writing, the impossibility of escaping or undoing writing, of accurately translating…

This is a fascinating book exploring the many ways graphic signs—especially those that have not been systematized—can be both a way of writing as well as a way of undoing (alphabetic) writing, in which it is best to just let the signs speak for themselves.

Comments

Post a Comment